Wilbur Mitts was 24 years old when he died serving in World War II. His torpedo bomber was brought down over the western Pacific Ocean on September 10, 1944, during the final year of the war. After a year-long search, he was declared killed in action and awarded the Purple Heart.

Seventy-nine years and one day after his death, Mitts was laid to rest beside family members in Seaside, the place where he grew up. His funeral took place on Sep 11, 2023, at Mission Mortuary and Memorial Park. Like all military funerals, it was a ballet of precision and grace. Six sailors in dress whites accompanied his casket, draped in an American flag, to his grave site.

The nonprofit organization Project Recover found Mitts’ remains after an extensive search, upholding the military’s promise to leave no one behind, and allowing the young aviator to come home eight decades later.

The funeral brought monumental closure to Mitts’ family, who wondered if this day would ever come. Diana Ward, Mitts’ niece, said his return has brought her family together. For a long time, she said there was a “lot of quietness” around Mitts and his death.

“I’ve learned so much about him. I feel like he’s coming together as the individual he was,” Ward said.

Ward never met her uncle — she was born three days after he died — but she feels a deep connection to him. Thanks to Project Recover’s efforts to find Mitts, her family grew closer, sharing stories about the young aviator.

At her home in Modesto, Ward studies photographs of her uncle. One captures a young Mitts rough-housing with his older brother. Another shows him smiling in front of his aircraft with his flight crew. They represent a tangible connection to her uncle, along with a scratchy record of him singing “Wabash Cannonball,” a popular song of his time.

For most of her life, she’s agonized over the what ifs.

“What other cousins would I have had?” she asked. “What other experiences would I have? What would I have learned from him?”

Ward said Mitts’ mother — her grandmother — would take flowers and lay them in the ocean every Memorial Day because he didn’t have a grave.

“I’m sure that not being able to even visualize or know where he was shot down was a big missing hole in her heart,” said Ward.

Her family now has a grave to visit, and long sought after answers, thanks to Pat Scannon, who leads Project Recover. The nonprofit works with the Defense Department to locate military members missing in action. It’s estimated there are more than 80,000 service members who are still unaccounted for. Scannon, a former military doctor, has dedicated his life to bringing MIAs home.

Scannon’s effort to find the crash site of Mitts began 20 years ago with the discovery of a submerged aircraft wing in a lagoon off of Malakal Island in Palau — the same plane Mitts and his crew were flying the day they were shot down.

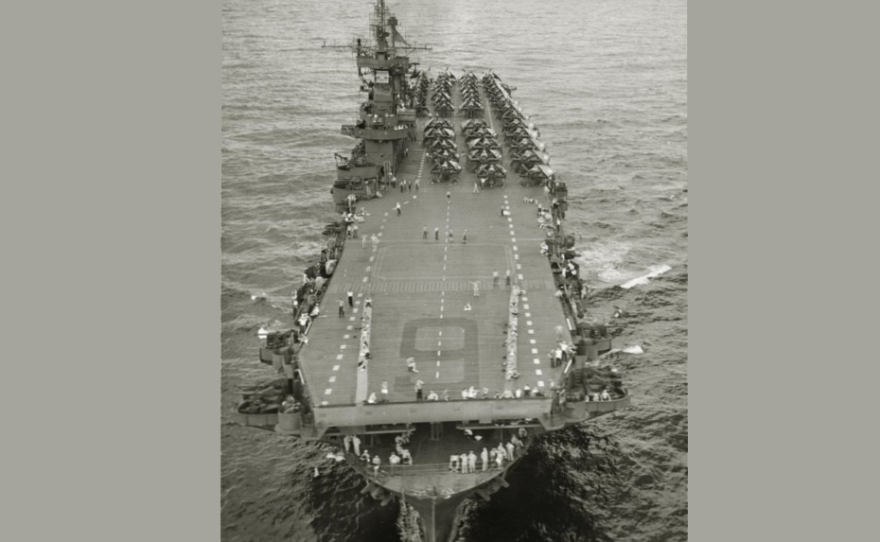

“We immediately recognized that as a wing of a certain type of aircraft, TBM Avenger, which was a torpedo bomber,” Scannon recalled.

The search that followed, using just scuba gear, was slow and unsuccessful. Scannon and his team never found the cockpit containing the crew.

“We found part of a tail section,” said Scannon. “We found other little bits and pieces.”

In 2014, Scannon’s organization partnered with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. With the use of underwater drones, the investigation picked up speed. Divers found the cockpit, and then, seven years later, began finding remains. More remains were found last year.

Dr. Carrie Brown, a forensic anthropologist who supervises the identification of recovered MIAs for the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, said identifying MIAs can take two or three years. She works out of a lab in Omaha, Nebraska, and although she didn’t work directly on the identification of Mitts, she is familiar with his case. Positive identification requires at least two pieces of evidence, she says.

“Dog tags, wallet,” Brown said. “How tall were they? How old were they when they died? We can also look at teeth.”

In Mitts’ case, DNA and dental records were used to identify him.

No other country goes to the extent of the United States to find, retrieve, identify and return to MIAs to U.S. soil. The military has 700 people working full time on locating and returning MIAs.

“It's a promise to our nation. It's a promise to our current day service members,” Brown said. “And it's a promise to everyone who was lost and their families who are still waiting.”

This story was created with support from the California Newsroom. Erika Mahoney wrote the digital version of this piece.