On a cloudy day in September, Ivano Aiello walks through tall grass at Elkhorn Slough Reserve, right next to the Moss Landing Power Plant.

“This is the place where I first found the metal,” he said. “I was out there three days after the fire.” Aiello is a marine geologist at Moss Landing Marine Labs (MLML), and the lead author on the Scientific Reports study.

He got to work quickly, testing the soil for heavy metals—specifically, nickel, cobalt, and manganese—which are used to make lithium-ion batteries. Using an X-ray fluorescence spectrometer, he was able to scan the top layer of soil and see the concentrations of metals. Then, he and his team took deeper samples—soil cores—and brought them back to the lab for analysis.

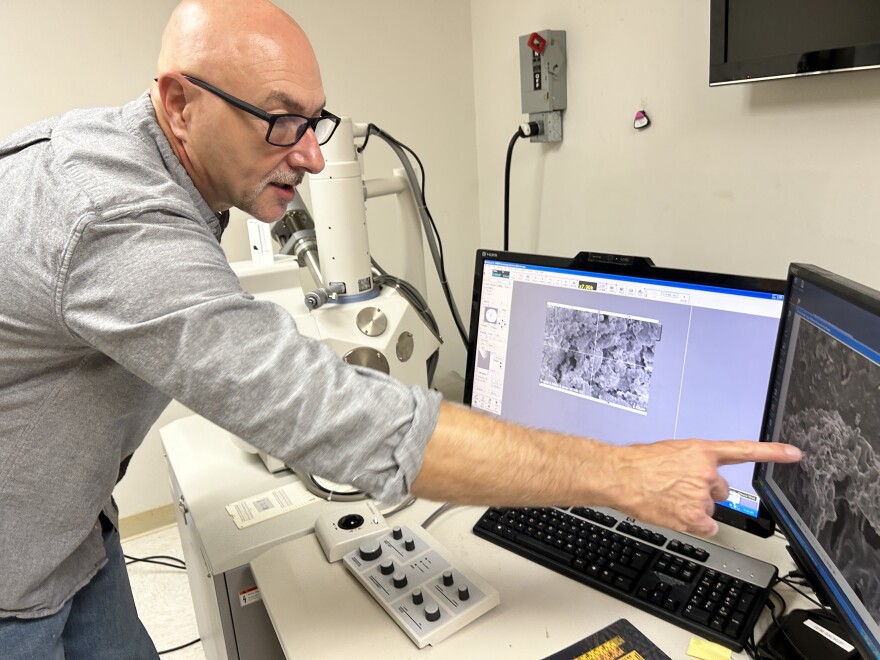

Aiello said he often sees whales in Monterey Bay from his office window at MLML. Just down the hall is the room where he has what he calls his “microscope on steroids.” It’s what allowed him to actually see the heavy metal deposits from the fire.

“This is one of those little metal balls that came from the fire,” he says, pulling up an image from the scanning electron microscope, which magnifies things up to a thousand times more than a standard optical microscope. “You can actually see them and you can zap them. And you can figure out what they're made of.” By zapping, he’s talking about having the machine send a burst of energy to the sample, which then reveals the make-up.

It turned out these nanoparticles were mostly made of cobalt, nickel, and manganese, the same metals he was getting high readings for in the field.

In his office, he pulls up graphs tracing the change in metal concentrations at Elkhorn Slough before and after the fire. It was notable that he was able to do this—he just happened to have background data, from 2023, because of other research. In one graph, the pre-fire levels of nickel and cobalt hovered near the bottom. After the fire, they both soared.

“This plot here is a really cool plot because it shows the two metals, nickel and cobalt, in parts per million,” Aiello said. “The two weren't correlated before. Now they're perfectly correlated.”

That correlation is an important point. After the fire, not only did both values jump, but they jumped at almost exactly a 2:1 ratio. It turns out, that’s the mixing ratio of nickel and cobalt in the cathode of a lithium-ion battery.

“I mean, it's almost like a fingerprint, right?” Aiello said.

This is one of the findings in the Scientific Reports paper.

“The paper demonstrates that there was a heavy metal fallout related to the fire,” he said. “The big picture stuff—we figured that out. Now we want to look at the long term.”

To do this, Aiello and his colleagues formed a research group. It's called EMBER, or, Estuary Monitoring of Battery Emissions and Residues. The scientists are affiliated with several institutions—MLML (which is part of San Jose State University), Marine Pollution Studies Lab (MPSL) within MLML, Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, Amah Mutsun Land Trust, Cal State Monterey Bay, and the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Their main objective is to understand how the heavy metals are moving through Elkhorn Slough, and whether they're accumulating in organisms like plants and fish.

The paper demonstrates that there was a heavy metal fallout related to the fire...The big picture stuff—we figured that out. Now we want to look at the long term.Ivano Aiello

One of the people responsible for overseeing the dissection of the sampled organisms is Autumn Bonnema, who works at MPSL.

“Our specialty here is trace metals,” Bonnema says as we walk into the lab. “Waters, tissues, sediments, soils, we're processing all of those samples here.”

Inside, two people are preparing fish tissue samples. In the corner, there's a machine that looks like a microwave, which is used to measure metals. “So you're looking at what the concentration of this metal is in that particular organism or water sample or sediment sample,” Bonnema said.

A lot of this research is taking place in uncharted territory.

“None of us are battery fire researchers by training,” said Amanda Kahn, who works with Bonnema on EMBER’s Biota Team, “I'm a deep sea sponge biologist.”

Kahn said it will be some time before they know exactly how the metals are impacting the ecosystem.

“We know that other metals, like mercury, can accumulate,” she said. “The reason we're still sampling nine months later is, is there potential for accumulation in the tissues? Then you can start to get growing concentrations that might not be lethal initially, but might have effects [that are] either sub-lethal or accumulate to a point where they are [lethal].” Which, she says, could have health implications for humans and other top predators, like otters.

“We get questions all the time like, ‘have you found anything yet? Am I safe to go and harvest mussels?’” Kahn said, “And we're like, ‘we can give numbers, but we can’t make that judgment call.’”

The Biota team released preliminary findings on Nov. 14 showing some indication that metals from the battery fire have entered estuarine food webs.

But the report said it’s too early to draw conclusions about whether the levels pose any threats to species living in Elkhorn Slough or humans who eat them.